On July 9, 1776, five days after its publication and shortly after the Declaration of Independence was read aloud to the people of New York City, New Yorkers tore down the statue of King George that had stood in Bowling Green since 1770 in a fierce demonstration of their new independence. The statue had a tangled history in the years that followed: much of it was melted down to serve as bullets in the Revolutionary War, while Loyalists in Connecticut smuggled a few pieces away to save: centuries later. One of George’s amputated arms was unearthed in 1991 and went up for auction in 2019. George’s horse’s tail went on display at the New York Historical in 2022 as part of an exhibit on the history of America’s difficult relationship with monuments. No one is quite sure what became of the monarch’s head.

This was how we treated tyrants in 1776 America: tearing them down, yes, but also squirreling them away as a show of loyalty, protecting and preserving these symbolic pieces because we knew they stood for something greater. To some, those pieces represented the colonial error of revolution; a longing for the system that was currently in place and which threatened to disappear before the eyes of upstarts. To others, they came to represent our history. Fractured and fragmented, splintering further all the time. Never, even at the very moment of our founding, all one story.

What then, to an American, is the Fourth of July?

I

Frederick Douglass was the first to pose this question: ex-slave, abolitionist, American, patriot. Douglass had a good eye for hypocrisy, and in 1852, he used it to excoriate his white neighbors in Rochester, New York, asking what on earth a celebration of freedom and independence could mean for the American slave, a man who had no freedom and no personhood in this nation brought forth by white landowners and slaveholders. For Douglass, the Fourth of July is a tragedy. “You may rejoice,” he told audience members. “I must mourn.”

America’s original sin, slavery has been called, a term which hails from the Garden of Eden and the fall from paradise. It’s an interesting metaphor, not the least because it dares to put the United States in the position of a lost paradise. John Milton and a legion of Christian thinkers have sought to redeem that fall by pointing to the redemption and the second coming of Christ. Theologically – that is, distinct from its comparison to American slavery – this narrative has spoken to millions, perhaps even Douglass himself. It’s nice to think that suffering has some higher meaning. But beyond the world of theology lies the world of history, and there we might take a different interpretation of the story for the sake of its use as a metaphor here in modern times. The Hebrew word for the serpent in the Garden is nachash, a serpent or a snake, and not a word secretly coded to mean the Devil or anything else. Sometimes a snake is just a snake. Sometimes there are mistakes that you can’t come back from, and you must instead face the consequences. When it comes to American independence and American history, we might fare better if we considered our original sin in the historical rather than the theological framework.

II

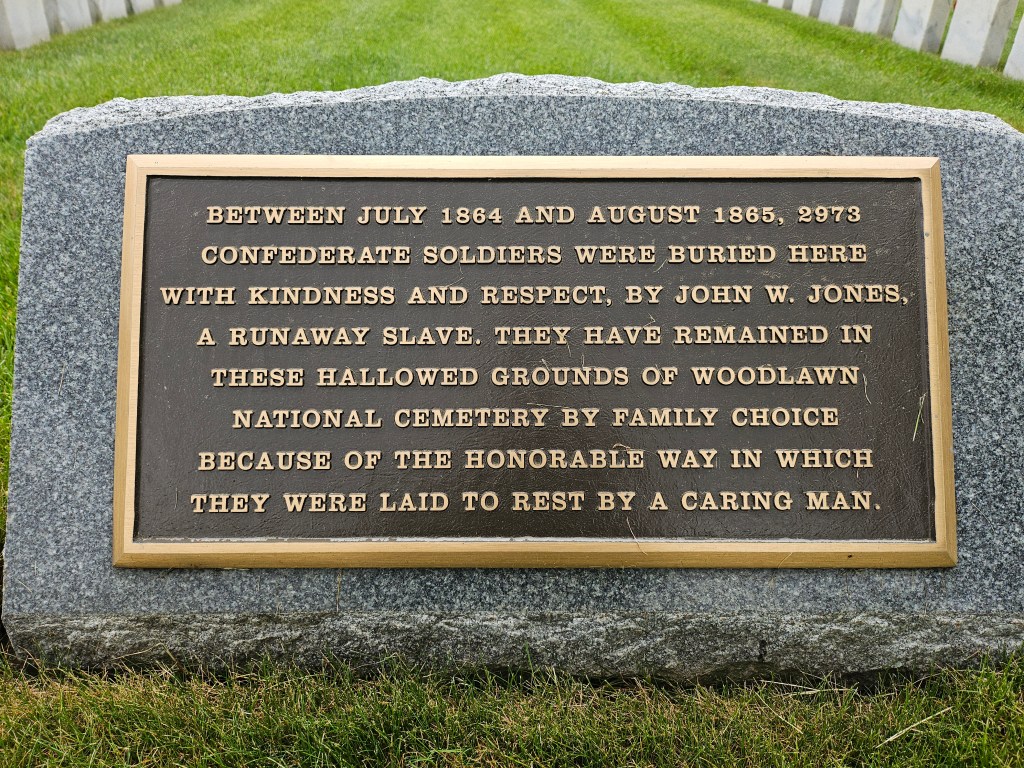

Not far from Douglass’s adopted home of Rochester, New York, another freedman would spend the years of the Civil War tending to Confederate prisoners housed in the small town of Elmira. John W. Jones had fled slavery in Virginia in 1826, working his way more than 300 miles north on the Underground Railway to settle in a free state and himself become an active member of the Underground Railway movement. By the start of the Civil War, he had helped nearly 1,000 souls to freedom, none of whom were captured and returned to the South. During the war, however, he offered aid to a different group: Confederate prisoners, sent north to keep them well away from the war. When conditions in the upstate New York winter killed nearly 3,000 of them, Jones recorded their names and their ranks, and supervised their neat and orderly burials in the local Woodlawn cemetery. He catalogued their belongings and sent their photographs and letters back to their families. In America’s first foray into total war, he preserved the identities of those who might otherwise have perished faceless, so much so that the site was declared a federal cemetery in 1877 and that the government could use his records to pin names on all but seven of the Confederate soldiers buried there. Jones received money for each burial, but he was not required to notify families or tend to graves. For his decision to do both, all but three families opted to have their sons’ bodies remain in Elmira.

To Jones’s eyes, fast approaching fifty, so many of those soldiers must have seemed only boys: teenagers too young to know any better, perhaps, eager to die for a cause, or desperately missing the safe borders of their lives at home. The awkwardness of youth has not changed throughout American history, be it the teenage revolutionaries of the colonial period or a boy who, at nineteen, still thinks a ridiculous name about testicles carries some power, some sign of manhood. We have not always had a taste for boy geniuses in this country. Even in the early 1800s, long before Congress was choked by aging lawmakers, the average age of the members of Congress was over forty. But as those soldiers lay dying, Jones offered them kindness and dignity just the same. Full of the vulnerability of youth, those boys might have wielded their cruelty and their whips against him harder than anyone had they caught him in different circumstances. Perhaps Jones, friend to all those terrified fugitives, knew that the best thing anyone can be offered at nineteen is not power or fame, not discipline or cruelty, but a simple affirmation of personhood, such a vulnerable thing as one enters adulthood.

Beside those 3,000 graves in Elmira, there is a statue to the youth of the Confederacy, erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in (1937). There is no statue to honor John Jones, only a small plaque. Kindness is not always repaid with kindness. This, too, is America. Did Jones celebrate the 4th of July, when it came around? Or did he look to January 1st, the day of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, or December 18, the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment? Perhaps it does not matter. After all, Jones actualized the central tenant of American independence far better than most of us: that we are all created equal, even when your fellow man does not treat you that way.

III

I have long had the habit of rereading the Declaration of Independence every year on the Fourth of July, but in recent years I have had cause to reach for in other moments. Best of all are the days I can teach it in my own classroom, introducing it sometimes for the first time to my students. Pay attention, I tell them. It is rare that you will get to read something that so completely left its mark on the world. Mindful that the Declaration was read aloud to many of those first Americans, that it was written to be understood by the people, I sometimes have students read it out loud line by line, parsing through the eighteenth century language to uncover these ideals that we are still working towards nearly two hundred and fifty years later. When, in the course of human events…

The Declaration begins by acknowledging that when a body of people choose to break from those who have gone before them, they must offer a reason for doing so – that to do otherwise would be a breakage with the dignity and bonds of fellowship we owe even to those with whom we disagree profoudly. It supports this stance with the famous words that follow its opening: We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness… So often we use these words to champion the rights of the huddled masses that have come to America’s doors. That is as it should be, for it represents the very best of this nation. But sometimes I find myself wondering whether I ought to be reminding my students that it applies to those with whom we disagree, too. Today it is ever more fashionable to mock our enemies. And too, the colonists did their fair share – ultimately, of course, they had to be willing to kill for these ideals. But first they also offered their reasons with dignity.

I bring other texts to the table when we look at the Declaration, too. We look at Frederick Douglass and his dismissal of the Fourth of July, at Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony’s appropriation of the text to make their claim for women’s rights. We read Lincoln’s interpretation of the Declaration against Alexander H. Stephens’s, the fight to extend humanity to more people and the equally stubborn effort to restrict it to the white race for all time. When we have time, I bring them texts from beyond America’s borders that reflect the long-lasting impact of the Declaration around the world: Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Women (1790), The French Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen (1793), the Korean March 1st Declaration of Independence (1919), the Indian Declaration of Purna Swaraj (1930). Maybe Thomas Jefferson meant exactly what he said when he wrote those immortal words; maybe he didn’t. It matters, I tell my students, and it doesn’t. What matters more is that people – people around the world, people for centuries thereafter – took them seriously. That means that we must, too. We cannot understand our history otherwise.

As we move into the list of grievances, the language for most grows unfamiliar, and I work with my students to identify what exactly each problem is referring to. These are the parts that Google AI’s summary will elide for you, explaining that it is a list of “detailed complaints” the American colonists had about King George. Google AI, like most of us, is not so concerned with exactly how the colonists defined tyranny because for so long that has not been the primary function of this document in our history or in the history of the Declaration in the world. Yet now more than ever, they bear a thorough reading.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them…

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands…

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power…

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:..

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever…

This was our definition of a tyrant, I tell my students. This, too, the world took seriously. Once.

IV

The Declaration of Independence is an imperfect document, like all historical documents are. Perhaps nowhere is this more apparent than in its treatment of America’s Indigenous people, whom it references only once: the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

If American independence was a tragedy for the enslaved, it is not unreasonable to suggest that it was a catastrophe for Indigenous people across the continent. Many fought with the British, throwing their lot in with the power that had at least sometimes shown itself willing to negotiate on fair terms. In the years that followed, the former colonists would push aggressively west across the continent, breaking one promise after another and slaughtering thousands in the name of American ideals. Join or Die, we might say, in the grimmest sense of the word. In their wake Americans built statues to these lost and vanished people, mourning their absence as a way of claiming their land. Such a pity that they could not sustain themselves in this bounteous place. How kind of them to show us the way before they vanished. How good of us to tend to their land in their honor.

That the land that Americans conquered, stole, and remade entirely – one might say, the second original sin of our founding – became a land of refuge and succor for many does not negate this point. Rather, it signals the many contradictions to come, written into the foundation of American history. I write this from Ireland, where American shores offered salvation for millions during the Great Famine. Millions more fled other wars, famines, and bigotry to settle in America, or to make their fortunes and improve the lots of their descendants. My own family, like so many other Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe, found prosperity in the New World, if only one looked past the quotas, the closed borders and the rejection of refugee ships of the World War II era, and the occasional attack on a synagogue. “To bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance” was a better deal than most Jews had been offered anywhere else, after all. Aspirational though we know these words to be, my ancestors and so many others took them seriously. Their adopted country did not always live up to these ideals. But at least they offered them.

Most Americans were not themselves descended from those select few who had signed the Declaration, or who had joined the fight for independence. Even if their ancestors were not enslaved or dismissed as savages, they lived many thousands of miles away from the upstart New World colonies, blissfully unaware that someday their children’s children would set forth for this unknown land that offered outrageous promises like free speech and religious liberty. But they, too, would reach for the Fourth of July when they came to the New World. They used it as a date to dedicate their own memorials, a token of their allegiance to their new home. They celebrated that independence in internment camps, rejoicing in a freedom that had not been granted to their own families and friends. They demanded, like so many before them, that we take the stakes, the promises, and the responsibilities of independence seriously, even though they knew firsthand the failures of this country to so many different people over so many different times. Failure to achieve those goals this time did not mean one could stop working towards them. A broken promise does not mean an absolution of a vow.

V

Did they know, those early revolutionaries, what this country would come to mean to so many millions? Surely not. And if they saw the America of today, with its many races and faiths, with women who wear pants and vote and hold elected office, with our lightning technology and our magnificent national parks, empty of their original inhabitants, they might very well be horrified. Then again, they might look to an impotent Congress and an obsequious Supreme Court, to the President who wants to be King, and think: this is not what I fought for. We will never know. They have left us only their words, and not their updated opinions. And we have tried to honor their ideals.

Some have done so by demanding that we live up to the ideals they set: Douglass, Lincoln, Cady Stanton, Anthony. Some have done so by modeling what that could look like themselves: John W. Jones, working to free the slave and to bury Confederate dead with dignity, consistent in his ideals in the face of an inconsistent and frequently immoral government. Many have taken to the streets, demanding an end to a tyranny overseas and at home. Still others have adopted these ideals and this history as their own, aware that mistakes have consequences, aware that some mistakes can never be fully undone.

Let us turn back to 1776. Rebellion was not the easy choice then, as well the colonists knew. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. Revolution is hard. Democracy is harder. Democracy means no easy fixes, no simple narratives. How could it mean elsewhere when it must attempt to balance the views of so many different people? How could anyone have thought that the United States of America would succeed at anything? Already in that era there were slaves and freedmen, an abundance of faiths, a steady flow of immigrants, an abundance of languages, a swirl of claims to an endlessly diverse land. Revolution was an insane risk. And yet: when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.

Revolution, in the eyes of the Declaration, was a necessity, not a choice. Democracy, the new Guard of the American republic, was also not a choice. It was hard and it was messy. But all the same, there was no other choice, no other way to ensure freedom from tyranny.

The Fourth of July is our legacy as Americans, our nation’s contribution to the world, whether we want that heritage or not. It is a time for a celebration of the best of America; it is a time to mourn and rage against all of America’s failures. But we must, as we enter this 249th year, understand it above all else as a warning. The definition of tyranny stands before us, and it has long been both our right and our duty to throw it off wherever we find it. We knew that tyranny for what it was, once. We must know it again.