After the 2016 election, exhausted from campaign work and horrified by the turn my country had taken, I took a week off before the next political races began to visit an old friend in France. Their family had moved to a town near the Swiss border some years before, and I had hoped to visit for quite some time. I had only once before been to Europe. We saw a whole range of things on a family road trip to visit some of their expat friends who lived on the other side of the country, but what I remembered most were the castles, and how France seemed to have more of them than they now knew what to do with. We saw castles that were overrun with commercialism, full of fake armour and jousting flags, and ones that were open and empty and that you could walk through entirely unsupervised. These ruins had been living spaces once, full of their own histories and purposes. Taken together in the twenty-first century, they posed a difficult question about the physical remnants of history. How do we decide what we do with what the past has left behind?

That same friend has now moved to the UK, where they are pursuing a master’s degree at the University of Leeds, and so we arranged that I would stay a few days while I traveled back down to London from Scotland. Yorkshire had certainly been on my travel list, but I admit that Leeds itself had not been – somewhat like its cousin to the west, Manchester, the only image I really had of it was as a manufacturing town that had suffered from the same postindustrial collapse that many of our Rust Belt cities in the States had done. It is not much of a tourist destination: even the city’s residents described Manchester as cosmopolitan in comparison. But it is certainly an interesting place to think about how we handle the ravages of history.

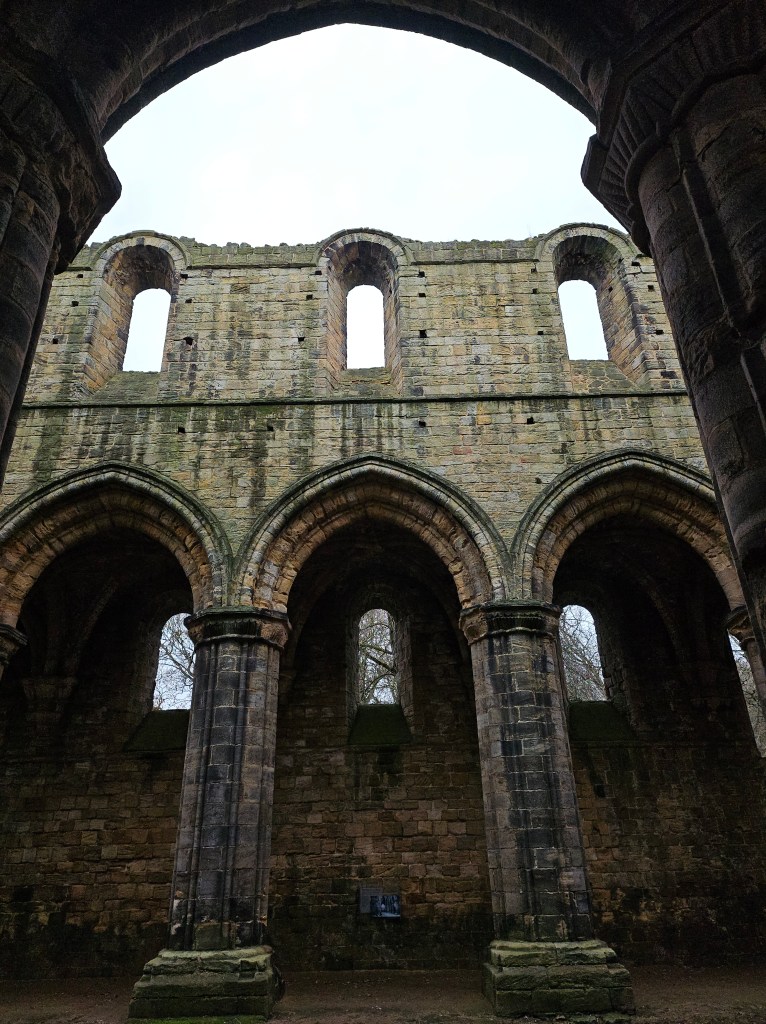

Leeds’s general approach to its history and many ruins is to render them usable. Perhaps the most impressive historical relic the city boasts is Kirkstall Abbey, one of the most complete Cistercian monasteries left in Britain. The Cistercians, an offshoot of the Benedictines, came to Yorkshire in the 1100s and quickly set up a number of abbeys and churches, of which Kirkstall wasn’t the most important, but has remained the most intact. It has an interesting history, including a period where two of its abbots had to be sanctioned for corruption (one had apparently organized a gang of monks to go out and terrorize the villagers), its completion of a fancy new kitchen just 10 years before the abbey was ordered closed by Henry VIII and his new Anglican church, and the period in the 19th century where the main road to and from Leeds ran… right through the church. (Honestly, it’s amazing that anything is left, when you think about it). Today the abbey is mostly closed off as a ruin, but the annual Shakespeare festival performed there through 2009, and since then there has been the occasional concert. Strangely, this constant use has helped preserve some of the abbey’s original majesty. We visited on a particularly quiet Sunday morning. In the dim clouds of December, the church threw off its somewhat sordid history and once more cloaked itself in the otherworldly ruins of time.

Leeds became a huge trade center at the start of the Industrial Revolution, as a mill town that converted and exported Yorkshire wool. Much of the modern downtown dates from the Victorian period or later, including the many covered shopping throughways (“arcades,” as they are called here) that liven up passageway through the city. (The standout is Thornton Arcade, which features rather risqué-looking figures from Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe, including Robin Hood and Friar Tuck, who ring bells on the hour. And to think, it was constructed 100 years before Men in Tights!). The city was dismissed even during the Blitz, where it escaped most bombing because it had few targets of interest. Although its fortunes took a downturn after World War II, today it is home to four universities and over 109,000 companies, boasting an extremely diverse population and economy. And fortunately, as my host was someone who actually lives there, I also got to see a little of the vibrant communities that are now thriving in Leeds.

On my first day, I tagged along to their knitting club’s holiday party – a good window not only into all the ways that I am woefully uncrafty, but also to how these small groups can help keep local businesses and charities up and running (this particular group meets in a café whose proceeds support people with Down Syndrome, and they offer crochet classes in the café every so often to help raise money). The following day, as my friend is also a member of the Leeds Guild of Singers, I went to their holiday concert in the nearby town of Adel, which is small and not particularly known for anything, but (since this is England) is still using their Norman-era church for worship and concerts. The church was built between 1150 and 1160, and as I sat through the rehearsal and watched concertgoers stream in to pack the place for the performance, I thought of how remarkable it was that the residents of this community have been coming here for the same holiday celebrations for nearly 900 years now, perhaps even singing some of the same songs. The church is tiny, and perhaps another town would have replaced it with a larger space by now. But Adel, at least, is more interested in using its history, and we were all the better for it.

We enjoyed other sites that have been kept up or repurposed and refinished around Leeds, too – the magnificent public library (repurposed now to also house a café and an art museum), the charming Abbey Museum across the street from Kirkstall that is packed full of all sorts of Victorian oddities collected from the town, the local department store (John Lewis) that still has a “Haberdashery” section, the Corn Exchange (now a shopping center for small businesses). Still, however cool Leeds is, there’s a lot that England’s largest county has to offer, and so we made sure to take a few day trips while I was here to see other parts.

Anyone coming to Yorkshire will of course want to see York, the great medieval center that is still a university town but now also a top tourist destination. There’s some weird connection with Harry Potter – although the movies weren’t filmed there, people have decided parts of the Shambles, the crowded and twisting medieval streets in the middle of town, look like Diagon Alley, and of course where there’s a belief there is also a market to capitalize on it – but the town is well worth seeing even ignoring that.

York’s approach to ruins, by and large, has been to freeze them in time to keep them from falling into ruin at all. We saw this in play almost immediately when we forewent the popular tea parlor Betty’s in favor of Parlormade, a scone shop in the Shambles. There we enjoyed a cup of tea and scones in a building that has been around since at least the Tudors (forgettable tea, but top-notch scones). The building was in excellent shape, but it bore the crooked hallmarks of its original architects, and it provided a blueprint for most of the rest of what we’d see in York: well-loved buildings, upgraded for the modern moment without forsaking their history. Outside, we met some of the people building this blend of history and the modern: representatives from the Yorkshire Birds of Prey Centre, who are themselves trained falconers but who recognize that the way to draw in donations is to allow random tourists to take pictures with their remarkable rescued owls. My friend wanted a turn, so we waited in line and learned about the Society’s dedicated conservation efforts. Not quite T.H. White’s The Goshawk, but not too far off: an ancient art preserved for new uses in new times.

We skipped York’s great cathedral, the largest Gothic cathedral in Northern Europe, because it was impossible to justify the expense: £16 just to enter, and £22 to climb up to the tower, with a concession of only £1 or £2 off each price because we were students. I noticed this was a general trend in York: there were student discounts because it’s the thing to do, but unlike most places, where those amount to a meaningful sum since that’s the point of a discount, they were only ever a pound or two, not enough to make much of a difference. Perhaps this is the cost of preserving your history entirely to support tourism: apparently you cannot forsake even a single visitor’s fare. I might have bothered, were it a place of worship sacred in my own tradition, or were my tolerance of churches not nearly exhausted this close to Christmas, as it often is (ruins are a different matter!). But as it was, we hung around the back door by the gift shop, caught a few glimpses whenever anyone came out, and declared ourselves satisfied.

Generally, it was fascinating to see buildings kept up so carefully, even if what we were seeing was a repaired version of what once was. The only exception to this was Clifford’s Tower, which is controlled by English Heritage and which I at least could enter for free, having signed up for a membership back in Tintagel. (Between the student discount and the foreigner discount, the membership paid for itself in about a visit and a half). Unlike the rest of the city, the tower (formerly a castle) really is mostly a ruin, with little to show the horrors or the triumphs of York’s history. Probably most infamous of those horrors is the mass suicide that occurred in this tower in 1190, when York’s Jews, hiding from a mob in the tower and facing death or a forced conversion, committed suicide rather than convert to Catholicism, a grim reminder that the county’s moniker, “God’s Own Country,” has never quite equally applied to everyone. History charged on without them, of course (England’s Jews were expelled wholesale one hundred years later), and the castle served as a home and a seat of power for another 500 years. Long in disrepair, the tower has now been outfitted with a viewing balcony and internal stairs that let you access the king’s latrine (an honor, I’m sure), efforts which left a bad taste in my mouth. Space is precious in England, and throwing away a perfectly usable castle over some minor bloodshed wouldn’t have made any sense to a nobleman. But still, nearly one thousand years later, perhaps we could concede that some things ought to be left entirely in ruins.

The surprise hit of the day, however, was the Fairfax House, a remarkably preserved Georgian home towards the edge of York’s Old City. I am not much of one for historical homes, usually, and this is certainly not my default historical era, but we were intrigued by the posterboard outside, which was titled “A Christmas Moustery” and showed a picture of a mouse dressed like a bandit. In addition to being the birthplace of Guy Fawkes, York is also the site where famed highwayman Dick Turpin was finally hung and buried, and to our delight, we discovered that every holiday season the Fairfax House writes a mystery into its holiday decorations where one can trace a mouse-sized, Turpin-inspired character through the home to solve a heist that Mouse Turpin has committed. (Like most Americans, I learned who Turpin was from the novel Good Omens, where one character has named his malfunctioning old car after the criminal because “wherever he goes, he holds up traffic” – probably that’s all you need to know about the original historical figure).

Bear with me here. We were ready to dismiss it as a way to entertain children, but within two rooms we had realized the genius of the plan. To set the scene, the house is filled with little felt mice – over 400 of them, we learned, most dressed and placed by the House’s volunteers. In each room you can read a testimony from one mouse in order to string together alibis and solve the mystery (in this year’s case, who helped Mouse Turpin filch an enormous ruby from Fairfax House), but if you just do that, you’re missing the point. The real fun is to examine the other 390 mice, who draw your attention to aspects of this remarkable home that you might otherwise have missed. They are engaged in the same habits that the original occupants of the house would have been, from scullery maids to scholars, and they highlight the careful preservation work that make this house known as one of the best-preserved Georgian homes in England. Mouse Turpin, in particular, is often to be found perched high above and overlooking the chaos, an element which draws your attention repeatedly to Fairfax House’s incredible ceilings. The mystery is fun (we did guess correctly, but we were told by the staff that folks are often misled by the unreliable testimony of one of the maids), but the real achievement is how carefully the whole display asks you to look at this home, for those – like myself! – who might otherwise not have bothered. Usually I get through a space like that in half an hour, tops, but we stayed for an hour and felt ourselves much richer for it.

Yorkshire abounds in things to see, but the one site that friends in the knitting crew recommended above all others was Whitby, the coastal town whose abbey ruins inspired Bram Stoker to use it as a backdrop for his most famous novel. I had never actually read Dracula, which of course was unacceptable if we were to visit, so I borrowed a copy and diligently worked my way through before we set out. (I really think there are aspects of this book that we have not plumbed enough in popular culture. Mostly, the part where the Count scurries down walls headfirst like a lizard.) Stoker staged Whitby as the place where Dracula, having commandeered a ship (and then eaten most of the crew) shipwrecks ashore in England, and first unleashes his horrors on the people of Britain. Whitby has really leaned into this, hosting a Goth festival every fall and breaking the Guiness World Record in 2022 for “largest gathering of people dressed as vampires” (1,369 of them, easily crushing the previous record of 1,039 set in Virginia). You might expect this to make the town a little gauche, but in fact, it is totally breathtaking. I will leave it to Stoker’s Mina to paint the scene:

“This is a lovely place. The little river, the Esk, runs through a deep valley, which broadens out as it comes near the harbour… The valley is beautifully green, and it is so steep that when you are on the high land on either side you look right across it, unless you are near enough to see down. The houses of the old town—the side away from us—are all red-roofed, and seem piled up one over the other anyhow, like the pictures we see of Nuremberg. Right over the town is the ruin of Whitby Abbey, which was sacked by the Danes, and which is the scene of part of “Marmion,” where the girl was built up in the wall. It is a most noble ruin, of immense size, and full of beautiful and romantic bits; there is a legend that a white lady is seen in one of the windows. Between it and the town there is another church, the parish one, round which is a big graveyard, all full of tombstones. This is to my mind the nicest spot in Whitby, for it lies right over the town, and has a full view of the harbour and all up the bay…”

Part of the appeal of Whitby Abbey to me was that its history is much older than Kirkstall’s: this site was first built up as an abbey in the 600s, and by a woman, no less. St. Hilde, the founder, achieved sainthood because of her miracle of ridding the area of snakes, but I think the real miracle she performed was hosting a synod that set the dates for Easter, since everyone knows organizing calendars and getting a bunch of people to agree to the same time is the highest kind of miracle. This version of the abbey was destroyed in the 800s by Vikings, specifically by a guy named Ivar the Boneless, a name that was never properly explained by the Abbey Museum. Wikipedia suggests to me that it was either because he had a skeletal condition, or that he had trouble with, shall we say, other kinds of bones, ones which might have left him impotent, if you catch my drift.

All jokes aside, the power of the Abbey’s positioning over the high cliffs of the North Sea was enough that another abbey and another church were built over the ruins again the following century, creating a space that flourished until Henry VIII’s religious “reforms.” The church about which Mina writes above in Dracula is a real place, leading to endless tramping from tourists. A sign reminds visitors at the entrance that “this is hallowed ground.” The Abbey radiates that feeling of sanctity, despite the violence it has seen (both real and fictional). One can understand how it spoke to worshippers time and time again over the centuries, whether they were Christian believers or those who worship art, stories, and the written word. Small wonder that it was rebuilt after its initial, terrible destruction.

People come to Whitby to see the Abbey, but there are other things, too: a museum to Captain Cook on the bluffs opposite the ruins, a small museum to the lifeboat that rescued passengers during a 1914 shipwreck (the Abbey was also bombed during WWI, and sustained significant damage to its western side), and of course, the sea, where we can all wonder and marvel at the things beyond our control. But the while benches along the bluffs and the quay point in all directions, the unquestionable majority are oriented towards the Abbey. Stoker is the most famous person to have been inspired by this view, but he was hardly the only one: there are paintings aplenty from the Romantic movement, and marvelous photography from the present. Between freezing the past and using it in full, Whitby reminds us of a third option: letting it rest, and drawing new life from it.

We do not have the particular problem of endless and easily identified ruins in the United States, a country whose pre-Columbian history was nearly wiped out with the diseases, massacres, and cultural extinction that early settlers and later government policies ravaged upon our physical landscape. But I think that for exactly that reason it is all the more important for Americans to grapple with the questions of how to handle the ruins that are left to us. Use them or preserve them? Draw from them hope or despair? Either way, we cannot ignore their presence, however faint they appear on our side of the Atlantic. Fortunately, there are models aplenty that may help us make use of our own ruins.

Epilogue: Bookstores, for the Curious

Leeds & York: York has a number of independent bookstores with both new and used offerings, but even in the off-season, they were so crowded as to not really be worth it. This was disappointing, but from the floor that we did explore before we gave up, it may not be the end of the world: I wasn’t terribly impressed with what they had on offer. In both cities, we had the best luck at the OxFam book-only locations, where you can unexpectedly stumble across very nicely bound copies of books that are nearly seventy-five years old. My friend walked away with a pristine copy of Rupert Brooks’s poetry from 1952. Overall, I’ve been impressed with the charity shops of the UK, which are probably on the same level as Goodwill or the Salvation Army (they have those here, too), but have generally stronger collections and whose proceeds go to better causes.

Whitby: I was charmed by the Whitby Bookshop, which offers all the usual new books in most departments, but has (of course!) every issue of Dracula you might ever have dreamed of, and a good collection of the stories it has since spawned inspired. The space is also its own delight, with the staircase so old and rickety that only one person is permitted on it at once, and a whole room dedicated to the work of local artists to avoid that book-tchotchke-book-tchotchke pattern that so many bookstores have fallen prey to these days.

A great post, and equally great pictures!

LikeLike