Perhaps not unlike many children my age, I first came to know Edinburgh through Harry Potter: the legendary place where J.K. Rowling had first dreamed up the boy wizard. Once, a visit to The Elephant House, where the story’s first chapters were written, would have been one of the highest pilgrimages I could make in the United Kingdom. And rightfully so, I think. I owe a great deal to Rowling. Her stories taught me, as they did many in my generation, about the power of our choices, even when our actions seem to have little effect on the wider picture. They offered me role models, particularly in the form of a bookish girl who could get along just fine with her classmates without sacrificing her grades. And it was thanks to Rowling, more so than anyone except perhaps my third-grade teacher, that I learned how to write. She told her readers that if they wanted to learn to write, they had to read: to read everything that came in front of them, from the nutrition facts on the cereal box to any book that passed into their hands.

I didn’t know whether I wanted to be a writer or not, but such advice came at a crucial time for me. I did not know how to read when I first encountered the Harry Potter books in kindergarten: my father read them to me first by necessity and then later as a family tradition. In later years, when I had learned to read and we encountered a word he thought I might not know, he asked me to define it and had me look it up if I did not know what it meant. Slowly, my vocabulary grew to encompass all the words that Rowling thought children could handle, words like “nonplussed” and “pugnacious,” whose definitions I knew, even if could not pronounce them properly. Meanwhile I was taking Rowling’s advice seriously, diligently reading food labels and newspapers, kids’ books and adults’ books and Harry Potter, over and over and over again. And when the time came that I actually tried to write seriously and not just for a school assignment, I found that Rowling had been right: I had read enough, and somehow, I knew what to do.

I generally subscribe to the death of the author when I read literature, and have enjoyed all sorts of works by people who were probably or (in some cases) documented as less-than-ideal human beings. I have my limits, but there is also the inevitable fact that historians must see books as authentic primary sources, however abominable some authors may seem to us now. But as most know, Rowling’s attacks in recent years on gender non-conforming individuals are causing real and tangible harm in the present moment and giving platform to beliefs that are actively endangering dear friends of mine, as well as a significant population across the globe. This seemed like a different kind of problem to me than the views of an author long-dead, whose work might perpetuate harm but whose voice can speak no longer. How does one deal with the reverse, where the work remains beloved by a generation but the author’s voice is what perpetuates harm? For all these reasons, the lure of Harry Potter tourism had long since died away for me. But Edinburgh and its foggy spires remain a center of literary history for reasons that long predate J.K. Rowling, and if there was one place in Scotland that I wanted to see, I knew this had to be it.

I arrived in Edinburgh with a mild cold (unsurprising, really, given how much travel I’d been doing) and spent my first two days wandering around outside so as not to inadvertently get anyone else sick. As anyone who has visited the city surely knows, Edinburgh’s heart is split into the New Town, which features the wide streets and careful planning that so shaped many American cities, and the Old Town, with its weaving alleys and backways that are the hallmark of medieval Europe. It’s not a particularly big center, and even with my cold, an hour and a half’s walk on Shabbat afternoon was enough to give me a basic run of the place. (There is a lot to be said, I think, for exploring a new city on a day when your phone is off – it forces you to learn your surroundings without Google Maps).

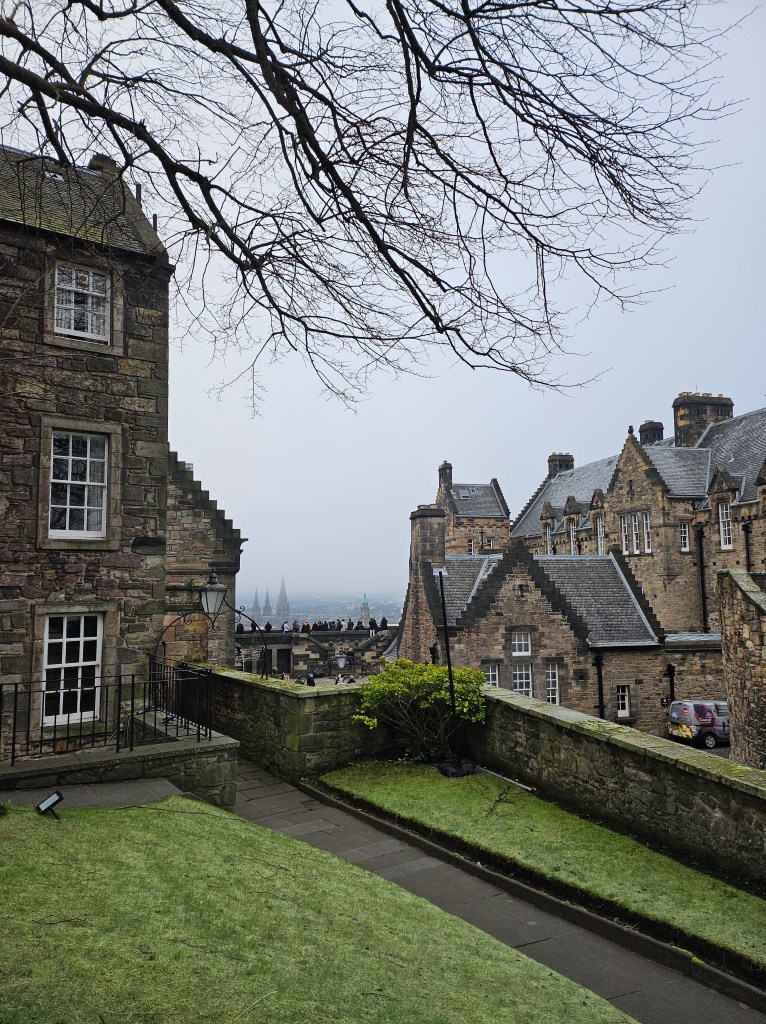

The best way to orient yourself to the city is to climb the stairs of Canton Hill, an extinct volcano that offers the best view of the city, at least in the view of Robert Louis Stevenson, a hometown author. Stevenson pointed out that while it’s not the highest spot, it’s the best to see both the cliffs of Edinburgh Castle and the hills of Holyrood Park, the two dominant landscapes that bookend Edinburgh’s Old Town. I found Edinburgh an extremely difficult town to photograph because of these endless peaks and changing heights: you can’t hope to capture the city in one or two shots, because everywhere you look the eye is drawn to something different. The easiest conditions were when it was foggy, and the fog made the decision of what to remove from the frame for you. The rest of the time, I considered it no wonder that many of its famous residents had sought words instead of images to depict it.

J. K. Rowling was actually born in England, but as the birthplace of renowned authors ranging from Stevenson to Arthur Conan Doyle, Robert Burns, and Walter Scott, Edinburgh was named UNESCO’s first City of Literature in 2004. Edinburgh is the only city in the world (so they say) to have a train station named after a novel: Waverly Station is named for Scott’s first prose novel, Waverly, which tells the story of a young man trapped between loyalties during the Jacobite Uprising. The city’s devotion to its literary heritage is made manifest with its massive monument to Scott, which stands 206 feet high and may be the largest monument dedicated to a writer anywhere in the world (Havana apparently has a competing claim with their monument to José Martí). Iconic as the structure is, it was perhaps a grim sign of the diminishing significance of the written word that the city has surrounded it with a garish Christmas market that stretches down into the park between the New and Old Towns and mars the skyline with things like a neon Ferris wheel and other amusement park rides. When the New Town was built, buildings were only constructed on one side of the brand-new Princes Street, so as to preserve the magnificent view of the Old Town skyline. But it seems commercialism is hard to resist these days, even when it comes at the expense of eclipsing the person who, more than any other, put Scotland’s name on the map in the nineteenth century. (Scroogey of me? Jewish! And anyway, cribbing from the Washington Post’s magnificent Alexandra Petri, one must respect a holiday that secured a temporary peace on the Western Front – but it only did that once, and Christmas shopping was not involved back then). I was shocked to realize that there is not a single bookstore on Old Town’s most famous thoroughfare, the Royal Mile, either.

To my surprise, this sense of contradiction followed me pretty much everywhere I went in Edinburgh. The National Museum of Scotland, for example, which is nominally meant to tell the story of the nation, instead depcits a place torn between its various histories. The problem is twofold. One, the museum space (opened 1998) was modelled in the style of a Scottish castle, with all its nooks and crannies and unexpected staircases and half-levels. This makes it very cool as a building, but (and I feel I can say this, having lived for a year in a dormitory Philadelphia architect Louis Kahn also modeled after a Scottish castle, which posed similar complications for different reasons) renders the space almost entirely unusable.

The nooks and weirdly-placed staircases mean that there is no straightforward, clear trajectory through the museum, which renders narrative difficult and navigation impossible. There is certainly a wealth of display space, but those spaces often do not fit together: I was confused to find a small section on World War I on the fifth floor, although the main exhibit about the World Wars doesn’t come until the sixth. Elsewhere, a gigantic stained-glass window can be viewed in full from the back across an open area, but visitors can only see the front side in small, constrained sections from individual floors. I noticed multiple visitors struggling to determine how to return to a floor they hadn’t realized they were exiting early by following a certain set of stairs; I myself accidently skipped most of the fourth floor exhibit and by that point was too overwhelmed with information to go back. Who has the stamina to find every single room? The exhibitions run to a staggering seven floors, which the main directory will tell you are organized on floors -1, 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6, with an optional rooftop terrace on 7 and a second and ground floor that can only be accessed from the first floor – I mean, what?

The bigger problem, however, is that the museum appears uncertain about how to define Scotland’s history. Prehistory begins not on the ground level but underground on level -1, and it runs from 8000 BCE to 1100 – in the Common Era! This period encompasses a good chunk of early Scottish civilization, not to mention encounters with the Romans and the Vikings, surely not who we would normally consider prehistoric peoples. It’s a particularly funny choice when you consider that Edinburgh spent the nineteenth century building fake Greek ruins (okay, maybe we could call them monuments in the Greek revival style, but you take my point) on top of Canton Hill to shore up their status as a great center of civilization and enlightenment, even though the Greeks never went anywhere near Scotland. But it’s telling, too: maybe the invaders you never had are easier to reckon with than the ones who actually turned up.

The most important invader, of course, is not any of the raiders whose arrival affected all of the British Isles, and that is why those other invaders are relegated to the basement – so that we can focus on the enemy at hand. When you enter from the ground level onto the first floor, as surely you are intended to do, you are greeted by a quote that defines Scotland first and foremost as not England and then, only secondarily, with values of its own:

“As long as one hundred of us remain alive, we will never on any conditions be brought under English rule.

For we fight not for glory, nor riches, nor honors, but for Freedom alone, which no good man gives up except with his life.”

The quote is from a 14th century declaration of intent, where the Scots upheld their commitment to remaining an independent people. But the museum covers this period and the one after it – where the Scots and the English were ruled under a joint monarch but maintained separate governments – in a single floor as well, devoting the whole of the remaining four floors (or… six? depends on how you count) to the period after Scotland became unified with England. And indeed, those exhibits become slightly more coherent, perhaps because they have a specific cause to rail against. It was a strange contrast to the Highlands, which seemed so comfortable with its pre-Jacobite history. In the Lowlands, it is not clear exactly who the Scots want to be. And I thought then of Edinburgh’s famous authors and their beloved creations, so celebrated here in the city… and about how many of those literary heroes live in London: Peter Pan (J. M. Barrie, born in Kirriemuir, Angus and educated at the University of Edinburgh), Sherlock Holmes (Arthur Conan Doyle, born and educated in Edinburgh), Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde (Robert Louis Stevenson, born and educated in Edinburgh).

This tension tracked to the National Museum’s sibling, the National War Museum of Scotland, which is housed within the grounds of Edinburgh Castle. The War Museum suffers from a size problem: enormous crowds come through Scotland’s most-visited castle every year (I shudder to think what it might be like in the summer, given how packed some areas were on a blisteringly cold day in December), and the Museum, confined to the architecture of the castle, is simply unable to hold them all. Cleverly, they have addressed this problem by offering a short chronology of Scotland’s wartime history in a relatively brief exhibit and then winnowing guests via two separate routes forward. One takes those who aren’t actually all that interested back to the gift shop, and the second goes to further exhibitions for those who are. The other problem, which is that a lot of Scottish military history consists of rebelling against the country of which they are now a part, is a little harder to handle. Luckily, the museum has devised a solution to that, too: it ignores the rebels Highlanders almost entirely. Instead, it highlights the history of the Highland regiments, which were recruited for the express purpose of building up loyalty to the Crown, and offers that as the whole of Scottish military history. Narratively coherent, yes. But not exactly a comprehensive story.

Edinburgh Castle is also home to the National Scottish War Memorial, which lies just up the hill. Opened in 1927, the War Memorial honors Scotland’s horrific 135,000 casualties in World War I, a war in which a full 11.3% of the population served. While it is not spared from the enormous crowds, it is mercifully handled with a greater degree of decorum than the War Museum (a low bar: the War Museum sells socks with tanks on them in its gift shop). At the War Memorial, there is nothing to sell, and visitors are asked to use low voices. Photography is prohibited – inconvenient for me as a researcher, but altogether appropriate in a space otherwise given over to tourism. The monument, which is a colossal chapel that features carvings dedicated to individual regiments and a bevvy of Scottish imagery, was so large that it changed the Old Town skyline, a decision which angered some but was felt by most to be a worthy honor for Scotland’s fallen soldiers.

Yet despite all of its nods to Scotland’s saints and heritage, it too feels a little torn between messages. There is very little Gaelic anywhere to be seen. The dedications also follow the classically British tendency to list officers first and enlisted men second (say what you will about the Americans, but I have always considered it a reason for national pride that the majority of our war memorials are organized alphabetically and not by rank). And there is a tense line between Scotland as a nation and Scotland as part of the British Empire. Battles of the Western Front are given prime real estate in the main room, while battles fought across the rest of the globe (Gallipoli, Palestine, etc.) are set off to the side rooms. In the center position of honor is the name Beaumont Hamel, a section of the line that was virtually wiped out at the beginning of the battle of the Somme in July 1916. Yet today it is the government of Canada that maintains that site in France – the heavily Scottish regiments from Newfoundland were also wiped out on that fateful day, and handing governance of the site over to an officially independent Commonwealth country seems to have been a more straightforward solution than allowing the Scots to shape the memory of such an emotionally fraught space .

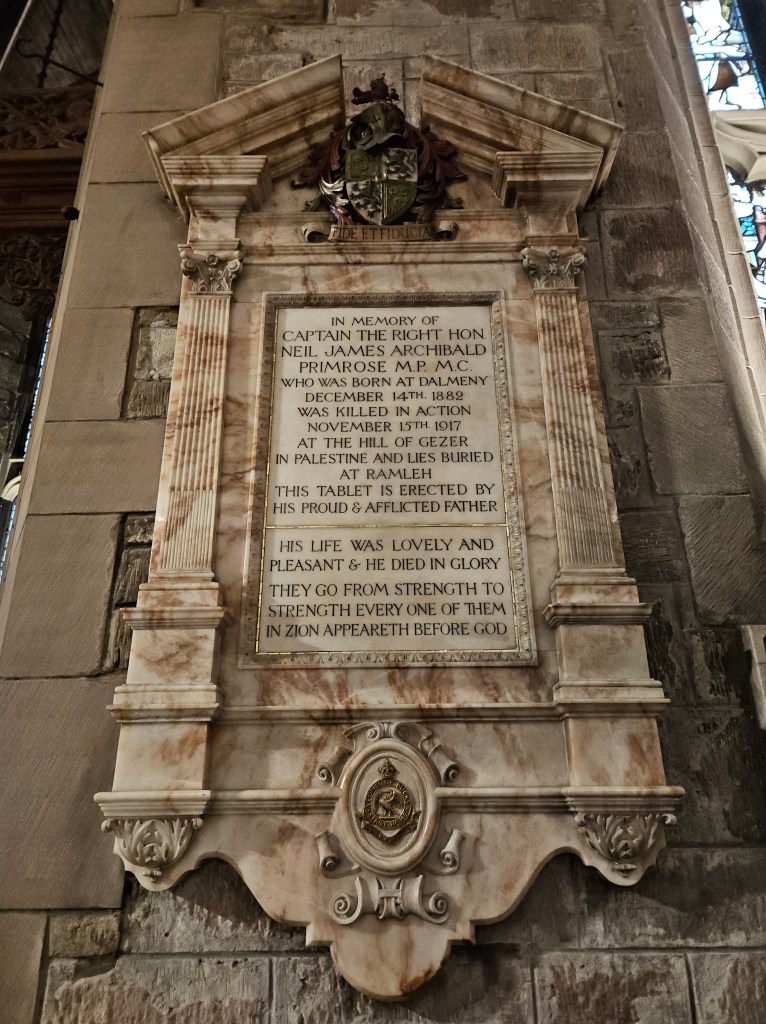

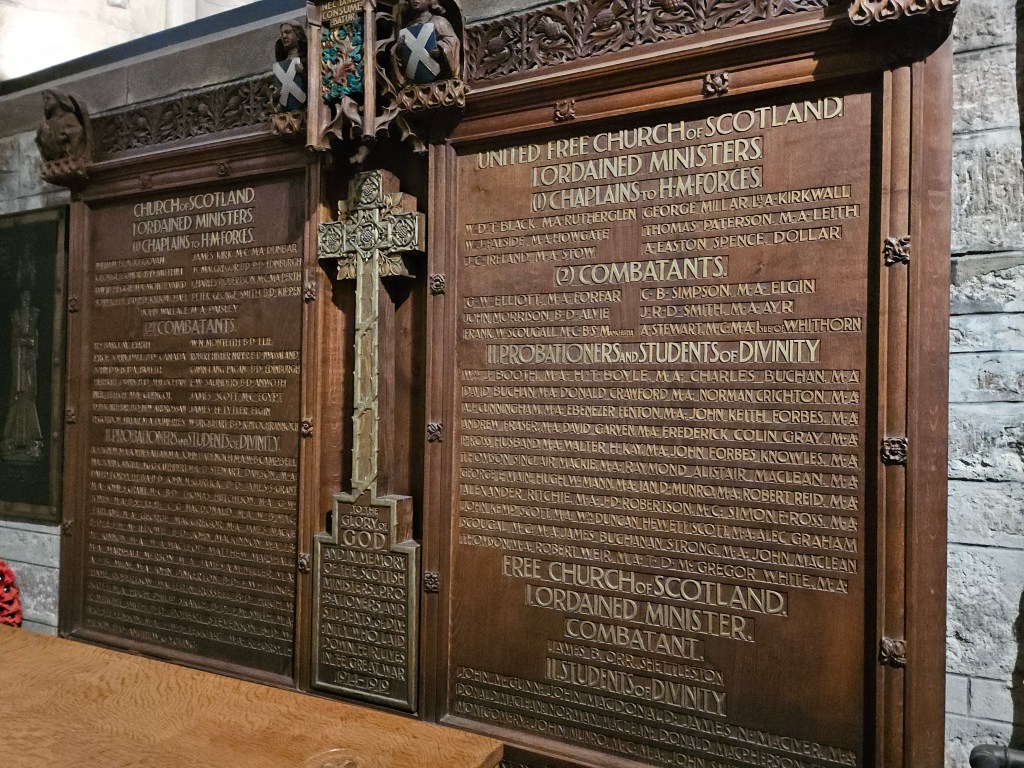

Like many national memorials, there is so much loss packed into this cavernous space that it somehow becomes difficult to see the terrible scale of the war. You can see it elsewhere in the city, most particularly in the churches. At St. Giles, further down the Royal Mile, I was struck by how many of dedicated plaques on the walls were to victims of the Great War: everyone from parents honoring children to regiments honoring their dead, from the church honoring its parishioners to French immigrants honoring the contribution of Scottish soldiers, with a wreath from Armistice Day from the French themselves. (The French, I have noticed, are much more gracious about this sort of thing than other nations. You can find thank-yous from them nearly everywhere, but you will never see one from the British). Proportionally, the Great War was recognized here in higher numbers than I had seen in almost any other church in the United Kingdom. I was most touched by a joint dedicatory plaque from three of the churches of Scotland: the Church of Scotland, the United Free Church of Scotland, and the Free Church of Scotland. (Don’t ask me what the differences between these groups might be; there was a helpful diagram explaining it all in the National Museum and I still couldn’t make heads or tails of it). As any religious person knows, these divisions between churches are often so fraught that members would die for their faction. That they came together in this space to honor their dead together struck me as a genuinely national expression of sorrow.

This, I think, may be the key to understanding Edinburgh. Visiting the Royal Botanical Gardens’ holiday light show, I heard John Williams’ marvelous composition, “Harry’s Wondrous World” floating through the trees, and walked forward to see a section of the path illuminated by floating candles in a clear homage to Hogwarts’s Great Hall. I had seen very little of Harry Potter in any of the city’s bookstores, nor had I felt much of Rowling’s presence in anywhere except the heart of the touristy centers. The original Elephant House is closed, having been gutted by a freak fire in 2021. It seems that the city has decided they can do without her, for now. But here I stopped to watch delighted children pass by and thought of how marvelous it is that Rowling’s creations continue to inspire joy and creativity, even if it is in spite and not because of her best efforts.

Edinburgh’s magic, and perhaps its source of inspiration for many of these writers, is that the city draws the wildness of Scotland right into its civilized center, from the monuments and homes built along the Water of Leith to the jagged cliffs of Edinburgh Castle. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Holyrood Park, the enormous combination of moors, an extinct volcano, lochs, and ruins that make it, in the words of one description I was reading, “a microcosm of Scotland’s scenery.” I began and ended my time in the city with hikes in the park – first to Arthur’s Seat, the highest spot in the park at 250.1 meters, and later to the edges of the cliffs that make the hills so startling. (Shoutout to Laird Hatters in London, from whom I purchased my latest wool cap this spring: not once did it budge from my head, despite the remarkable wind on the exposed hills. Those guys know what they’re doing!). It is a beloved feature of the city, a remnant of wilderness frequented by hikers and joggers, but open to anyone who might wish to undertake the half-hour hike to the summit – a summit named not for any of the early Scottish leaders, but for a legendary English king. It seems that whichever history Edinburghers look to, whichever narrative they embrace, they love this city and its wildness, its fog and its irreconcilable stories. I understand. I loved it too.

Epilogue: Bookstores, for the curious

As previously stated, for a city known for its literature, I was shocked by the bookstore layout in Edinburgh. There are no bookstores along the Royal Mile. (What is the point of a mile of shops if you can’t buy books?). Although there are a respectable number of libraries in the area, including the National Library of Scotland just a block from the Royal Mile, I didn’t see a bookstore until Day 4 of wandering around, which horrified me. You have to venture a few streets into the Old Town to find the secondhand shops, and the same goes for the New Town (all right, there’s a Waterstones at the very edge of Princes Street, but still). Here are the ones I found that I liked best… but with the admonition that somebody needs to open a bookstore on the Royal Mile itself stat. I think we could sacrifice one of the 500 kilt shops.

Secondhand: I was pleased to see a stretch of West Port Road in the Old Town that has a few different secondhand/rare book stores, sort of like how Charing Cross used to be. Armchair Books is probably the most popular of the three, although from photos I have seen in their heyday, their stock seems a little low right now.

John Kay’s Shop: as indicated by the name, this is more for people who like the aesthetic of books than the books themselves, but if you need a quick copy of a classic book with fancy binding (think Dickens, Stevenson, Austen, Scott) they have a very curated selection that can be of specific and targeted use, and it was the closest bookstore I found to the Royal Mile proper.

Topping & Company Booksellers: hands down my favorite of the bunch. They have a large and variable collection (enormous travel section, with distinctions made between maps, literary travel, and guidebooks), they preserve all hardcover books in a dust jacket in case you’re inclined to keep yours in mint condition, they have a wide collection of signed copies (not my thing, but cool!) and you are permitted to use the ladders they have scattered all over to get to the books on the high shelves. Funny enough, the book I wanted just happened to be way up there…

Further afield, Golden Hare Books offers a closely curated selection (including a lot of books I’d never seen before, always a good sign) in the lovely neighborhood of Stockbridge, which is worth seeing on its own. Directly across the street, Ginger and Pickles specializes in books for children and has a very dear window display.

Lovely and enlightening as always! As a really old person I would suggest turning off Google Maps more often. 😉 Just the other day I mentioned to JP how much I missed road trips guided by a paper Rand McNally road atlas! From the time I was tiny and my parents gave me “my very own copy” in the back seat of our station wagon, onward to 36 years later to our honeymoon, I loved looking for the little tiny roads to “meander along” as my dad always said. Safe travels.

LikeLike