Hearken, landsmen, hearken, seamen,

to the tale of grief and me,

Looking from the land of Biscay

on the waters of the sea.Looking from the land of Biscay

over Ocean to the sky

On the far-beholding foreland

paced at even grief and I…– A. E. Housman, “The Land of Biscay”

Many rom-coms want you to believe that when you get stranded in a tiny village somewhere in the UK, your savior will be a young handsome man who falls in love with you at first sight (thus trapping you in that town forever, but for nicer reasons than you were originally stranded, I guess). In my experience, however, the people who really come to your aid in moments of crisis are middle-aged women (all hail Florence, my savior when my car got towed in France last spring!). My hero a fortnight ago was a female taxi driver, who drove me and a whole crew of other stranded travelers through Devon as far as Exeter, where we could all board trains to our final destinations. Thus I escaped Okehampton after all, and thanks to a woman who insisted on charging all of us a single combined fare – £10 per person, probably less than it would ultimately have cost me to take the train. Look for the helpers, as they say.

And it was a good thing that I got out of there. I was meant to spend the week based out of Bristol, traveling to nearby towns like Bath and Cardiff and perhaps further afield into Wales if I felt up to it. But Shabbat morning, news came through from the States that my paternal grandfather, long ill with the lingering aftereffects of a heart attack and COVID-19 (still, even now, claiming victims, though we refuse to think of it), had finally passed away, and my plans changed.

Jewish custom is to bury the dead as soon as possible, but it is also forbidden for observant Jews to travel on Shabbat. I got the news as soon as I woke up – I had left my phone on for updates, as we suspected the end was probably close. But once I had the news in hand, there was little else to do until sundown. One may break the laws of Shabbat for the living, the rabbis teach, but not for the dead. So I set out to wander the city of Bristol for the day, secure in the knowledge that there was nothing I could do, and that walking is usually the best way to organize my thoughts.

Bristol is a city, from the little that I saw of it, that is working to come to terms with its past. A port city, it was the site from which the first major English explorer of the Americas, John Cabot, set sail. (Of course, John Cabot, whose real name was Giovanni Caboto, was, like Christopher Columbus, actually an Italian hired to explore on behalf of another country, in this case by Henry VII of England, but – details, as they say). The event was commemorated in Bristol in 1897 with the construction of a massive tower on one of Bristol’s highest hills. At the top of the tower, you can find maps indicating the distance to other famous cities and one arrow pointing to Canada, 4,000 miles away, which Cabot reached sometime in 1497. It is still unknown whether he reached Cape Breton or Newfoundland, and he seems not to have stayed very long, but that hardly matters – in the politics of memory, what matters is that Cabot sailed only five years after Columbus and also that he found something, whatever it was.

Bristol’s status as a port city also made it a major player in the Transatlantic Slave Trade, a history which went largely overlooked until 2020. I was deeply moved – if somewhat astounded – to see that since then Bristol Cathedral has been putting serious work into uncovering this ugly history and setting it on display for visitors. Much of the Cathedral’s money in the 19th century came from slavers who had been paid out when Britain abolished slavery in 1833, and many slave traders from earlier eras are honored on its walls as patrons. The Cathedral has undertaken the careful work of pointing each of these individuals out and highlighting, where possible, the enslaved people who were hidden behind each of these names. A new plaque near the entryway honors one such family, and ends with a fierce rejoinder:

TRANS-ATLANTIC SLAVERY

WAS A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITYBLACK LIVES MATTER

YESTERDAY

TODAY

TOMORROW

The Cathedral is clearly aware that some may accuse them of not doing enough and spells out future plans for reconciliation work and further permanent installations. But still – it was more than I had seen anyone else do, and they cannot be the only cathedral in England that profited from funds like these. For a city busily erecting honors only to their earliest explorer barely more than a century ago, it is a meaningful gesture, all the more so because it is clear that it comes from a genuine desire to engage with this difficult past, and is not merely an effort to sweep the whole issue under the rug.

There was of course more I would have liked to see, but the sun sets early in England this time of year. Once it was dark, I gathered my things and caught a train to London. I flew to JFK the next day, and was in Rochester, New York by Monday morning.

He was not always an easy man to love, my grandfather. He liked to turn even the simplest of conversations into an argument, a tendency I only recognized as a speech pattern rather than a natural antagonism when I began to study the Talmud in my twenties. In everyday life, for those of us who did not grow up in a yeshivish neighborhood like Brooklyn was in the 1930s, simple statements about the weather are met with agreement or additional insight, not a rejoinder about how if the weather wasn’t this way, then you would have to say something different, nu? But when I first opened the Talmud and read the hypothetical arguments about whether or not one can sound shofar on Rosh Hashana from the depths of a pit, and what happens when the shofar blower in question is half in the pit and half out of the pit, and whether it matters what time of day he is blowing, and on and on and on, my grandfather’s method of communication began to make a little more sense to me.

My grandfather did not study much Talmud himself; he knew little of his immigrant parents’ mame loshon, Yiddish, and he did not attend services much when I knew him. Yet he came with my grandmother, and then later alone, to our Passover Seder every year, and occasionally I gained other insights into the ways that Judaism had shaped his life and his identity. Once I made a joke about all my Jewish friends growing up to become doctors or lawyers, and his tone turned suddenly sharp. “Don’t say that,” he said. “Don’t say that.”

My grandfather was a pediatrician, and he continued to do medical work officially until 2022, and unofficially right until the end of his life. It was not until that conversation that it occurred to me that his road to becoming a doctor might have been a thorny one. Later I learned that the Jewish quotas at the University of Pennsylvania, his undergraduate alma mater, had likely prevented his advancing to their medical school. (In the 1930s, some twenty years before he might have applied, Penn took only ten Jews for its class of several hundred students. Others kept their quotas even lower, at four or five). That he got in to a school at all is a testament to his intellect – by the post-WWII years, approximately 75% of all Gentile applicants were admitted to medical school, but the number of Jewish applicants admitted had plummeted to 25%. At Cornell, which insisted on limiting its Jewish medical students in proportion to the Jewish population of New York state, 15% of Jewish applicants were admitted, compared to the Catholic rate of 25% and the Protestant 35%. And so, despite his Ivy League education, my grandfather undertook his medical degree at Upstate Medical College in Syracuse, New York. He never complained about these circumstances, at least not to me. But I wondered after that conversation how much the situation might have rankled him, and how much the norms of his era prevented him from expressing this frustration.

The funeral was short, and the tributes we heard were fond and sincere: it was evident that even at 91, his life had still touched many others, and that people felt he was worth honoring even if it meant standing around outside in upstate New York the afternoon before Thanksgiving. When we returned to the house, and in the days after, I sorted through some of his books, finding among them the classics of English literature, and several detective novels set in Scotland and England. I am not of the school that travel is a cure-all – the poem from which I borrowed this post’s title, A. E. Housman’s “The Land of Biscay,” tells the story of a man walking the docks of the French bay who sees a sailor from a distance and imagines how much better the other man’s life must be, only to have the sailor ask him whether he knows of help for his own grief. One of the realities of travel is that everywhere you go you see people as well as places, and those people have many of the same problems that you do. But fresh air, new trails to walk, new places to see – those, I thought, might at least give me a little space to process and to think. And so I returned to the United Kingdom.

I had planned originally to ease my way north, but in addition to my time in Bristol, I had also cancelled a few days in the Lake District, and so I picked up my trip via train (train travel being another inherited love from my grandfather) and went straight north to Scotland. It was an eight-hour ride to Inverness (short by American standards, but long enough that you can get a sleeper car if you want), the so-called capital of the Scottish Highlands. Situated on the River Ness, Inverness is the fastest-growing city in the UK, and it is also the only city in the Highlands, making it the necessary transit point for anyone trying to go anywhere else. You can see what there is to see of the city in a day: the northernmost diocesan cathedral in mainland Britain, a fantastic bookshop, a small city museum that explains the local history and features a rotating art exhibit. But most people come to see the Highlands themselves, and for that you have to leave the city.

I took my first day trip to the place that surely everyone must go when they’re in this part of Scotland: Castle Urquhart, a spectacular ruined castle on the shores of Loch Ness. If you’ve seen any films with shots of Scotland, or read any coverage about the famous monster, you have probably seen it – as the only ruin directly on the shores of the loch, it gets a lot of attention. I am not a Nessie Truther myself, but one understands as you drive by the eerie mists on the loch and see the verdant moss that sprouts on all the trees and much of the stone, why there are people who want to believe (did the X Files ever do a Loch Ness Monster episode?). 755 feet deep in places, the Loch Ness holds more water than all the lakes in England and Wales combined, and it is deeper than considerable portions of the North Sea. No matter how well we document it, we may never really know all that goes on there.

But more than that, Urquhart is interesting as a symbol of Scotland, a capsule of what’s going on in the Highlands in miniature. Most of what we think of as Scottish today, I discovered in the Inverness Museum & Art Gallery, is actually the culture of the Highlands, rebranded and marketed out for a wider audience in the Victorian Era. Kilts, bagpipes, tartan patterns – it’s all from here, although most of it has passed through some commercialism en route. How and why this occurred has to do with the collapse of the Jacobite Rebellion at Culloden in 1746, the last battle fought on British soil (and only few miles outside Inverness). Following the defeat of Scotland and their subsequent absorption into what is now the United Kingdom, both Scots and outsiders sought to distinguish Scottish culture from English culture, and they leaned on what had already been local to the Highlands.

Castle Urquhart was destroyed precisely so that it could not be used in the Jacobite Rebellion, but it was one of the five castles that refused to cede to the King of England during the Wars of Scottish Independence some centuries before and this has given the castle special status – not necessarily in Scottish memory, but in those who like to romanticize Scotland and what it was. (Admittedly, never have I been more in sympathy with the cause for Scottish independence than when I watched an Englishman on his way into the castle blithely say to his companion, “I’ve been to loads of castles in England. Have you ever been to an English castle?”) Most of what’s left of the current settlement dates from the 1500s or later, and its hold (and that of Nessie) seems stronger on the international imagination than on the Scots. But still, right at the shores of Loch Ness, one can understand why the castle would hold such a place in global memory. Loch Ness is a part of the Great Glen, the deep rift that separates the north of Scotland from the rest of the island that makes up England, southern Scotland, and Wales. In that way, the Castle symbolizes a time, far beyond human history and memory, that the Highlands stood truly alone.

Most of the areas around Inverness, including Loch Ness, are really best accessed by car – you can take a bus, but as I discovered on my way back home, the buses really run on a “when we want to” sort of schedule. Google Maps of course cannot be trusted, but neither can the local apps, be they the helpful QR code left in the station to track when the next bus is coming through, the website’s Bus Tracker, or the national FirstBus app. After waiting an hour and a half in the cold to get back to Inverness, I decided that I’d carry out the rest of my trips by train. Luckily, ScotRail services a line from Inverness to Aberdeen, and there was plenty to see along that route for a day trip.

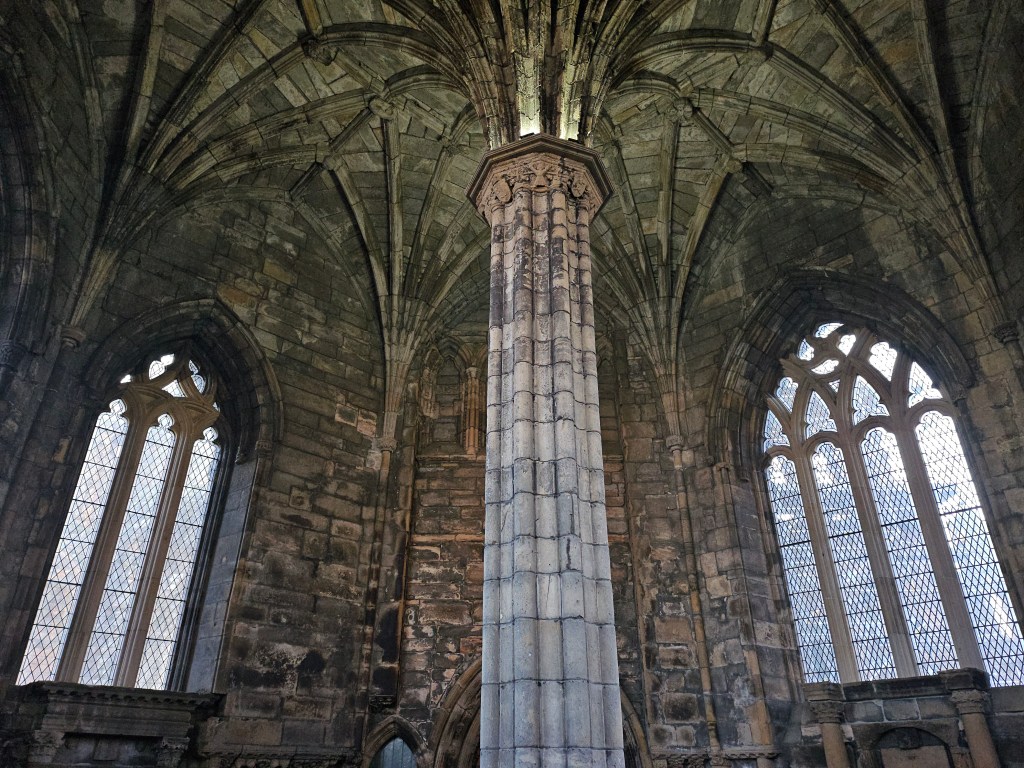

I picked two towns: Elgin (pronounced, for those of you know Elgin, Illinois, with a hard “g”) and Nairn. Elgin was first put on the map for the death of King Duncan (yes, that Duncan) inside its castle following his battle with the upstart earl Macbeth on the plains of Pitgavney several miles north. Most of Shakespeare’s story is myth, but it has a grounding in truth that is all around this landscape: there is a real castle of Cawdor (closed for season, alas), and a real Duncan and Macbeth did exist, although Macbeth’s rule was closer to two decades than two months. Elgin also hosts remarkable ruins of the cathedral that once made it a center of religious life in the region until the Protestant Reformation made its way to the North. Technically you have to pay to get in, but I asked if they had a student discount and they let me in for free, so let that go to show you that it’s always worth checking – or that everyone everywhere knows how dire it is to be a student these days, take your pick.

I was lucky enough to have full sunshine when I visited, but it is the kind of place that will move you regardless of the weather. With only its skeleton remaining, you get a sense that you cannot get from complete cathedrals about how remarkable they are as human endeavors. Surrounding the physical ruins were spiritual ones: the site is still an active cemetery for the very lucky few, but many were buried there long after the cathedral had officially fallen out of use. I thought of my grandfather again as I read the headstones. As with all cemeteries, one’s gaze is drawn first to the young who died before their time. Many cemeteries I have visited in the States have specific sections dedicated to young children and infants who died in the years before we were able to reduce infant and child mortality. My grandfather, in his work as a pediatrician, is one of the many people we can thank for the dedicated care and research advances that have helped make those days a more distant moment in our history. He was born in November 1932, that fragile time in the Great Depression when FDR had been elected but not yet taken office. Child mortality rates were already dropping by then, but over the course of his professional career they continued to drop, moving from thirty-five in 1,000 children in 1955 to only seven in 2020.

My last stop of this trip was Nairn, a charming little seaside town that many people visit in order to see the bottlenose dolphins that live in Moray Firth, the inlet that leads to the North Sea. December is not the best time to see them, so I came just to see the Firth itself, perhaps because as a child of the Great Lakes, I cannot resist a chance to see open water. Both my paternal grandparents loved the ocean, although I think they preferred warmer climes like Myrtle Beach to Scotland or even Lake Michigan. We found, when we began clearing the house, whole jars of seashells. As my grandmother was not Jewish, my immediate family has adopted the custom of leaving shells on her grave instead of stones, an homage to her background as well as ours. I picked up a shell for her and a stone for my grandfather, which I will hold onto until the time comes that I can visit their graves once more.

My grandfather did not read most of my academic work, but he did read all of my travel dispatches, or at least the ones I wrote from Europe this spring. I was fortunate to be able to discuss them with him this Passover, the last time I saw him. I had worried, when I decided to take this trip, that something like this might happen. But still I went, because travel is a great privilege, and not everyone is able to undertake it. Perhaps part of our obligation, then, when we go to see the world, is to share it with those who cannot go in turn. Not in the manner of John Cabot, and all those who followed him to plunder the world they had just discovered. But perhaps in the manner of Bristol Cathedral – to engage with what we meet seriously, to bring a small trace of what we find back home, and to link the world a little more closely together than it was before.

In memory of Dr. Robert Chavkin, 1932-2024.

Epilogue: Bookstores, for the Curious

All four of my grandparents were and are great readers, and along with messages from friends and family, it is stories that sustain me in times like these. Here are a few bookstores I noted along the way, should anyone find themselves in any of these towns.

Bristol: Stanford’s is actually a London-based chain known for their maps, but the Bristol chapter in their Old Town specializes in children’s books, which I found totally charming.

Inverness: a must-see in Inverness is Leakey’s Second-Hand Bookshop, which is housed in a former church! Not only do they have a fantastic reference and nonfiction collection, they will buy books off of you if you are, like me, not in a position to lug them around with you, and I have to hand it to them for their bravery in keeping an honest-to-goodness wood-burning fire in the middle of the building to help keep it warm.

Nairn: just at the end of High Street in Nairn is Nairn Books, a charming little place with an excellent local collection (they apparently also stock books in Gaelic). Leakey’s fiction offerings are a little weak, particularly when it comes to Scottish authors, so I was glad to find an alternative place where I could pick up work by and about the locals.

Eli – You continue to amaze me with you insights and your words. You bring honor to Bob’s memory.

Sending love.

LikeLike

Eliana, You never cease to amaze me but this particular writing touched me in so many ways. For someone who can no longer travel THANK YOU (!!!) for sharing everything. I treasure every footstep I take with you. Love from Elgin, Illinois 😉

LikeLike