By far the most exciting thing I did in London this week, over and including seeing a very old friend for dinner, doing the actual research that will hopefully shore up my future career as a scholar, and visiting a number of excellent bookstores (recs below), was seeing David Tennant on the West End, where he is currently starring as Macbeth.

I have a perverse love for Macbeth. Probably it should not surprise anyone at this point that I prefer Shakespeare’s tragedies over the comedies (and the histories that end in tragedy, like Richard III, over the nominally happy ones, like Henry V). Maybe it’s the pessimist in me, which likes the reassurance on stage that in fact, sometimes things don’t work out. More likely, I think I’m drawn to the pronouncements on human nature and mortal life that Shakespeare’s tragedies produce, and the gift he had for making you pity even the most awful of people (Richard III is a good example) in the hands of the right actor. I like to think that this puts me in a long line of amateur Shakespeare fans, those of us too poorly-read to know any better but fond of Shakespeare all the same. The most famous of these (of course) is Abraham Lincoln, who once declared in a letter to a Shakespearean actor, “I think nothing equals Macbeth—It is wonderful.” Lincoln was famously obsessed with the idea of ambition, being himself an extraordinarily ambitious man, and he was drawn to Macbeth’s story as a kind of cautionary tale. But when his letter about his own ideas of Shakespeare went public, he was broadly ridiculed in the press. Amateurs are amateurs, even if they are the President.

David Tennant was a wonderful version to get to see not the least because he is himself a Scot, and the production seemed determined to take all the pent-up years he’s spent having to put on an English accent and channel that into making this production the most Scottish adaptation possible. But he was also a totally mesmerizing stage presence, even to the point that when Malcolm was delivering his dutiful sermon about restoring righteousness to Scotland while Macbeth lay dead at his feet, my gaze was drawn not to the living souls who were to make Scotland whole once more, but rather to the sprawled actor playing dead on the ground. Malcolm is probably better for Scotland, one can’t help but think, but Macbeth was so much more interesting. (I spared a thought for the American electorate, yes. It is no brilliant insight to think that our present trouble stems in part from confusing reality with a television show a Shakespeare play. Of course the carnage Macbeth leaves in his wake can only be reduced to a source of fascination because he… isn’t real).

This production also played up the Macbeths’ childlessness, a feature emphasized by Lady Macbeth’s apparent headaches that sprang up whenever Banquo’s son Fleance appeared on stage; Macduff’s anguished howl, directed at the absent Macbeth rather than the present Malcolm, that Macbeth “has no children” when he hears of his own sons’ murder at Macbeth’s hands; and perhaps most of all use of the boy who played Fleance as the terrible voice of Hecate in Act IV. Here, too, it was difficult not to think of present parallels. Childlessness is a tragedy for anyone who wants children, but it is a political problem primarily for monarchs, not democratic leaders. After all, it is kings who need to ensure their own blood sits on the throne after them, carrying forward their seed and their ideas. The sneers about childless cat ladies and the like of our own era reflect the disdain our reigning political party feels for those who are still stupid enough to believe in the wisdom of relinquishing power and handing it to someone else’s children.

David Tennant has always struck me as a gentle soul, and this tendency came out even here, in his portrayal of one of Shakespeare’s cruelest villains. It is easy to play Lady Macbeth’s growing madness over the depth of her sins in perfect inverse to Macbeth’s growing conviction that what he has done is just and necessary, but Tennant offered Macbeth’s famous “tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” soliloquy between choked sobs, as if his heart were breaking. Perhaps that is the real appeal of Macbeth in this day and age, I thought: for all its cruelty, both its chief villains have multiple paralyzing moments of remorse, and the consequences eventually catch up to them. Remorse is not in fashion these days. It is hard to imagine hardly anyone in our present moment rueing that they could not respond “amen” when their victims cried “God bless us!”

I did other things in London this week, of course. I learned a great deal about the history of the Imperial War Museum (located in the building that was formerly Betham Hospital, a mental institution, there are still bars on some of the staff windows on the third floor), wandered the V&A, attended a Remembrance Week concert given by the BBC Singers, finally made it up to Hampstead Heath after several failed attempts on previous trips. But since I have had the great fortune to visit London before, I decided to prioritize venturing further afield. I have other regions I’m hoping to target later, but this week, I focused on the South Downs, a region famous for its crystal-clear chalk streams, which compose some of the rarest ecosystems in the world.

(A word here is perhaps merited on the UK’s marvelous National Rail system, which I’ve been using to get to all these places. Anyone planning to travel here in the future should skip the fancy passes they offer to foreigners that are good for four days of rides in a ten-day period or whatever: when I actually sat down to do the math, most of them aren’t worth it unless you plan your whole itinerary around them. Instead, the National Rail offers railcards to nearly everyone that you can take advantage of whether you are a UK citizen or not. There’s the 26-30 Railcard, which I signed up for, granting one-third discounts on all train tickets; there are options for those younger than this and for anyone above the age of 60; there is even a “Companion Railcard” that allows you to sign up with a friend or a spouse and receive a discount whenever you take the train together. Sorting through the railcard options is a much better use of your time and money than trying to route a perfect counterclockwise, hop-on, hop-off journey on through Scotland).

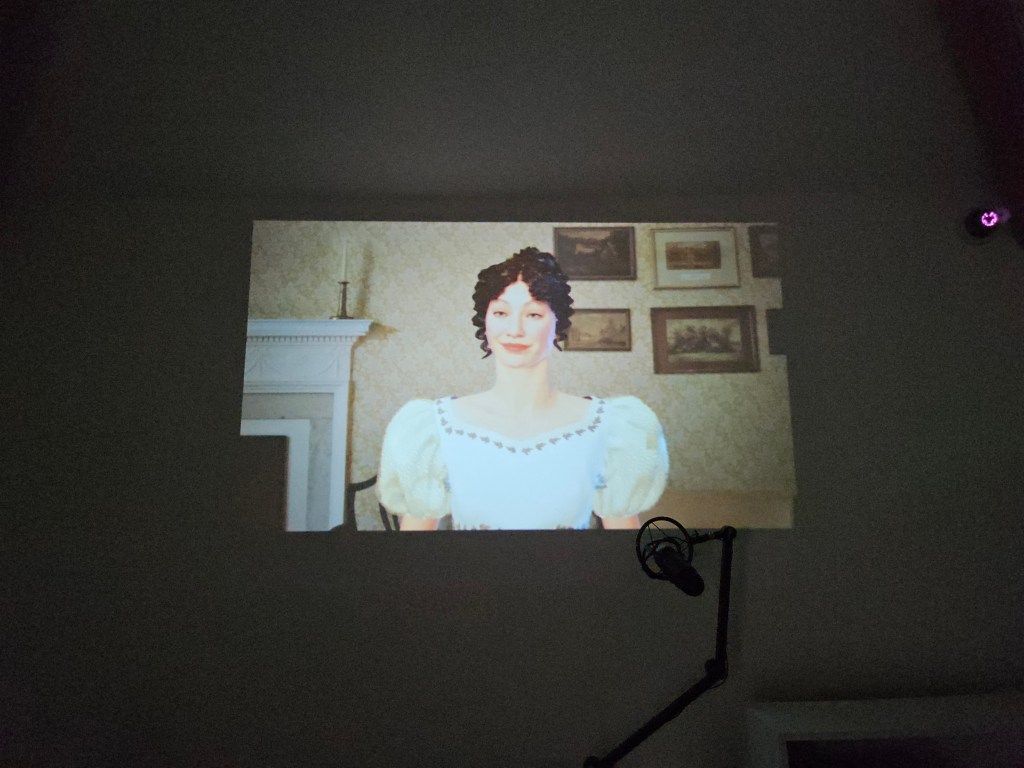

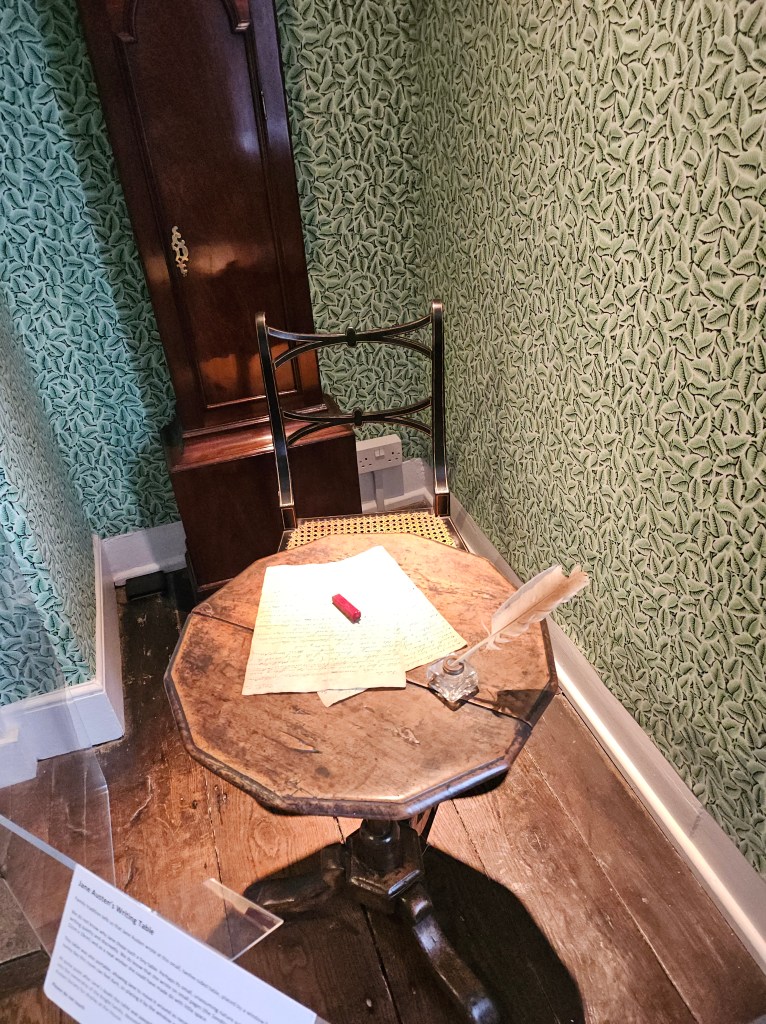

One of Britain’s most beloved authors was a resident of the South Downs: Jane Austen, who lived in the town of Chawton for her eight most productive years, during which all six of her novels were published, and three were written in full. You can take the train as far as neighboring Alton and then pick up a bus, but it seemed much more fitting to walk the two miles to Chawton, in honor of all of Austen’s endlessly wandering characters. The house itself is a simple affair, a usable amount of space rather than the endlessly stretching English manor. I found it altogether charming, an impression that lasted until I went to their research center and encountered an AI version of Elizabeth Bennet blinking down at me from a nearby wall and waiting for me to ask her a question.

The day after the election, a friend of mine commented to me that she thought one of the unaddressed reasons for the political sea-change was the onset of artificial intelligence. Uncertainty about what our jobs will look like in the coming years, about what professions will survive and which will change irreparably, about what art will look like and how we will formulate our own thoughts – the full landscape of AI’s implications is something many are not yet considering, at least, not on a broad enough scale. (“Alas, poor country – almost afraid to know itself,” says Ross in Macbeth). Not only can my university students get by without writing up their own thoughts about Pride and Prejudice, these days they can also have AI summarize it for them so that they never have to read it. But what a loss that would be! I first read Pride and Prejudice in tenth grade, with absolutely no idea of the plot (in fact, I had mixed it up with Atonement, probably because Kiera Knightley starred in both around that time) and I can still remember the shock and horror I felt for poor Lizzie in the high school cafeteria as I read Mr. Darcy’s botched proposal. Rare is the book that will preserve such a moment for you for so many years. What a shame it would be for future students to never experience it.

And honestly, what on earth would you want to ask an AI version of Elizabeth Bennet? Isn’t the whole point that she is whatever we imagine her to be? (I would like to note here that WordPress now offers the option for me to generate AI images for these posts – please know that these photos, however poor, are at least all mine). Feeling that such a thing would be a disgrace to Austen’s memory, I left without speaking to the avatar and instead turned down a public footpath I’d noticed on my walk in, one that leads into South Downs National Park and gives you a sense of what walking the country might have been like in Austen’s day. No doubt there are digital tours of such things these days, too, but I feel quite confident that the experience still pales in comparison to the real thing.

I was amused to note upon my return to London that evening that the busker in Oxford Circus, a violinist, was playing a Rondeau by British composer Henry Purcell, a piece that most people today are likely only to know because it was adapted for the soundtrack of the 2005 film version of Pride and Prejudice. Funny that the reason anyone should know it now is because of Austen and the world she created – a world that has enriched millions of lives, though she herself never married nor had children.

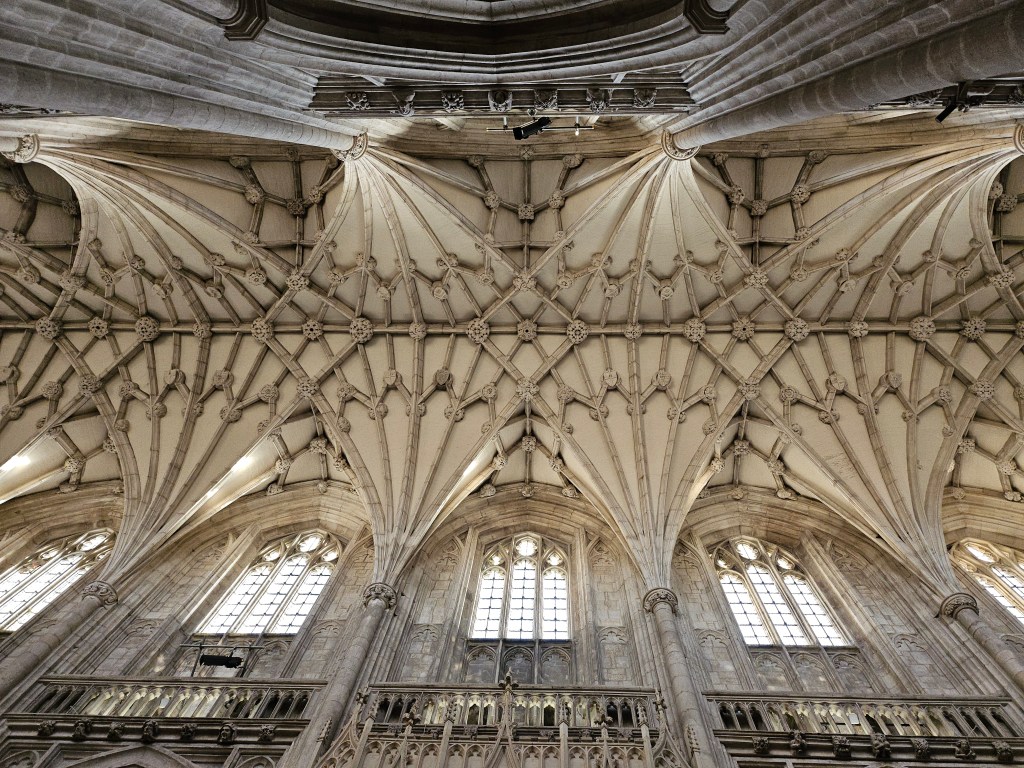

My other stop in the South Downs was Winchester, which happens to be where Austen is buried, but which I ventured to primarily to see for its nature and its great medieval cathedral, the largest of its kind in the world. For much of the Middle Ages the bishops of Winchester were kingmakers, and the cathedral, begun in 1079 and finished in 1532, symbolizes this status. I don’t know what it is about English cathedrals that I find particularly entrancing. Perhaps it’s the fact that I recognize much of the history that lives in their walls. Perhaps it’s also that English cathedrals tend to let in sunlight, unlike the beautiful but sometimes oppressive stained glass of St. Chapelle in Paris or the Duomo in Milan. I found Winchester Cathedral particularly heartbreaking because it is the spiritual home of the Hampshire Regiment, which sustained colossal losses during World War I. There is a full book of names honoring fallen soldiers from the regiment, along with individual memorials dotting different parts of the building. Each long list, when you find it, is by itself enough to bring tears to the eyes.

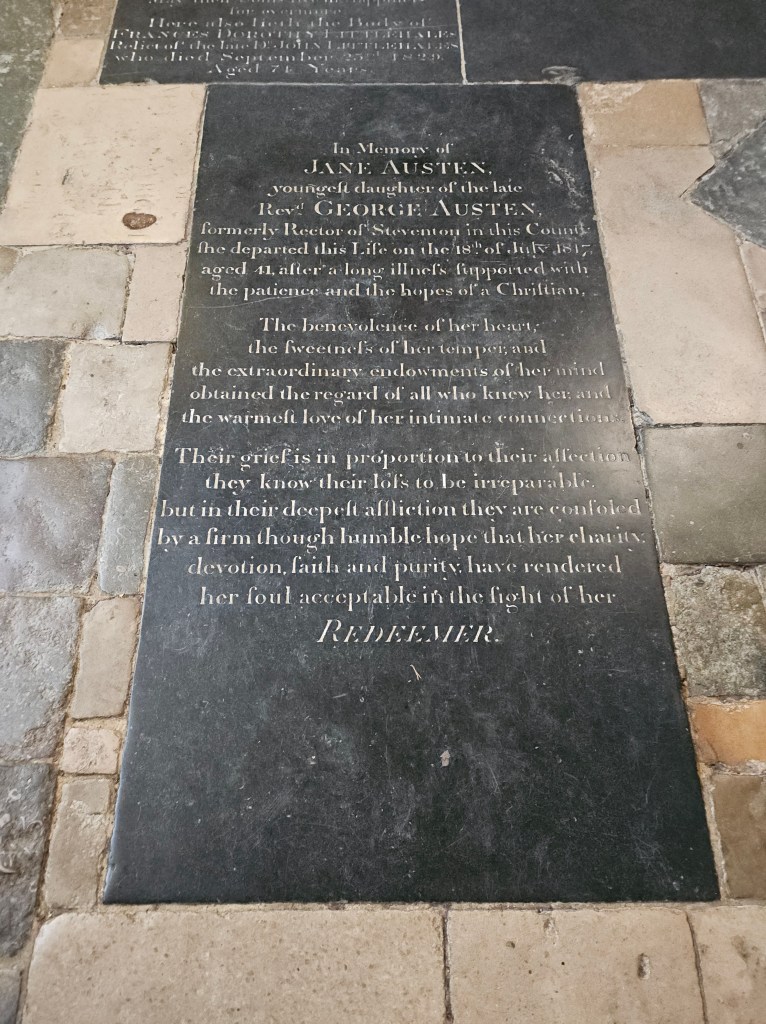

Austen herself is buried in a grave that makes no mention at all of her bestselling novels, a reminder of what was important about being a woman in the early 1800s. As she had no children, she is remembered primarily as someone else’s daughter and as a good Christian soul. Later her fans came together to dedicate a stained-glass window in her memory, but it is supposed to call to mind the Christian side of many of her characters, and if you, like me, associate the “Christian” aspect of Pride and Prejudice mainly with the hopeless Mr. Collins, you will begin to see why it feels a little lacking. There are, however, flowers kept fresh in the nave near her grave, along with a journal, which is packed full of missives beginning Dear Jane from Austen’s fans around the world. Of all the tributes I saw in Winchester and in Chawton, this seemed by far the most fitting.

Winchester Cathedral has a particularly remarkable character to thank for its continued existence: William Walker, a diver from the early twentieth century. I was mystified at first when I encountered a bust of a man labelled “William Walker M.V.O. Diver” outside the front of the cathedral and had to look him up. It turns out that four hundred years after its completion, the cathedral was in danger of imminent collapse, because those lovely chalk streams and peat soil of the South Downs had raised the groundwater level too high. Left alone, they would have sucked the stone into the waters underground. Working entirely on his own, Walker made daily dives into this water, six hours a day, five days a week, in complete darkness, for six years in order to shore up the foundation of the cathedral. The concrete foundation he laid along the cathedral’s southern and eastern walls stabilized the cathedral enough so that workers could take over above ground and reinstall its foundation. He is honored in Winchester as the man who “saved the cathedral with his own two hands.”

Walker never worked on treasure dives, instead using his skill for emergency rescue work and other construction projects, like the building of tunnels. He died in the influenza pandemic seven years after completing work on the cathedral. He was, I think it’s fair to say, about as real-life of a hero as they come. And we learn from Walker, as we have learned from the craftsmen and women who have spent the last few years carefully restoring Notre Dame in Paris, as we learn from David Tennant and Shakespeare and Jane Austen, that there are (at least for now) some jobs that only a person can do. To which I would say: thank goodness for that! I for one can live without an AI-generated Elizabeth Bennet, Macbeth, or really just about anyone else for a little longer.

Epilogue: Bookstores, for those inclined

I have no money to spend on fine dining, but I can’t travel without books, so this is where my spare change goes instead. Here were some favorites of the past week, whether I actually purchased anything there or not:

London: Waterstones and Foyle’s are wonderful, but for cheaper options, try Skoob Books by the University of London. Their collection is all used, and they offer a 10% student discount. For those overwhelmed by the choices available at the big stores, I enjoyed Daunt Books (I went to their location in Hampstead Heath, but they have a number of stores). Their books are organized by region, regardless of whether they’re fiction, non-fiction, or another genre, which I found mixed things up nicely. For those who prefer specialty bookstores, Persephone Books is dedicated to bringing popular books by women authors back into print, and Gay’s the Word has an excellent collection of queer literature and an outstanding legacy of advocacy work they did with Welsh miners against Margaret Thatcher back in the ‘80s, a story which was retold a few years ago in the movie Pride.

Winchester: P & G Wells is located next door the house in which Jane Austen died, and they have a whole section dedicated to her honor, as is only appropriate. They also had a wonderful natural history selection focusing in part on the unique landscape that is the South Downs.